Teach Vision to Middle School Students with Gizmos Investigations

Teaching vision can be one of the most engaging units in your science course. Students use their eyes every moment of the day, so they’re naturally curious about how vision really works. What’s going on behind the scenes with light, color, rods, cones, and the brain to create the images we see? With the right interactive science tools, you can turn that curiosity into hands-on discovery, making vision a unit where students move beyond memorizing parts of the eye to truly grasping how eyesight works.

Why teaching vision matters in middle school science

Vision sits right at the intersection of life science and physical science, which is part of what makes it powerful (and challenging). You’re asking students to understand microscopic structures like rod cells and cone cells, invisible processes like light waves, and big questions about how vision works at once.

Eyesight and vision naturally connect to three-dimensional learning, including the Science and Engineering Practices, Disciplinary Core Ideas, and Crosscutting Concepts students encounter throughout the year. When taught well, vision helps students see how structure supports function in the human body and how light and color influence what we see.

It’s also a unit that sparks curiosity. Students are genuinely interested in questions like:

- How do I see the things around me?

- Why do animals see different colors?

- What makes objects appear to be different colors

- What causes colorblindness?

- Why do dogs see fewer colors than humans?

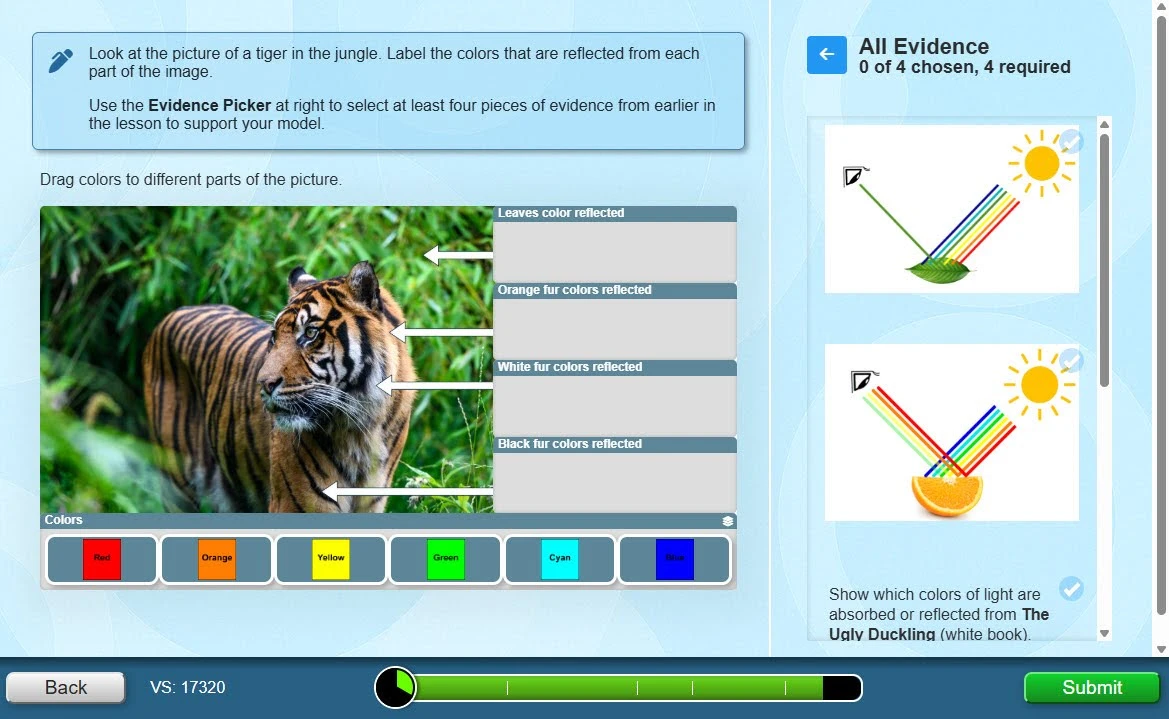

- How do tigers stay hidden from other animals despite their bright orange color?

Real-world examples, like animal camouflage in nature, give you instant hooks for engagement. Gizmos Investigations are designed with middle school science in mind, helping you turn questions into meaningful, standards-aligned learning experiences.

What students need to know about how vision works

How does vision work? Before students can explain animal camouflage or color vision differences, they need a clear mental model of how vision works. That means understanding both the physical structures of the eye and how light interacts with those structures to create what we see.

Light, color, and the brain

Students also need to understand how light and color work together. Objects reflect and absorb different wavelengths of light, and those wavelengths determine the colors we see. To make it concrete, connect color to everyday observations. When light hits an object, some wavelengths are absorbed while others are reflected (or transmitted). The color students see is the light that reaches their eyes, like red light reflected from an apple or green light from a leaf.

The structure and function of the eye

Help students understand the major human eye parts and recognize that vision only miraculously works when multiple parts work together.

Keep in mind some key vocabulary terms when teaching students about vision:

- Pupil: An opening in the center of the eye that allows light to enter.

- Cornea: A transparent layer at the front of the eye that protects the iris and pupil.

- Lens: A transparent, rounded structure that focuses light that enters the eye.

- Retina: A sheet of light-sensitive cells at the back of the eye.

- Rod cell: A light-sensitive cell in the retina that does not distinguish different colors.

- Cone cell: A light-sensitive cell in the retina that can distinguish different colors.

- Optic nerve: Carries visual information from the eye to the brain.

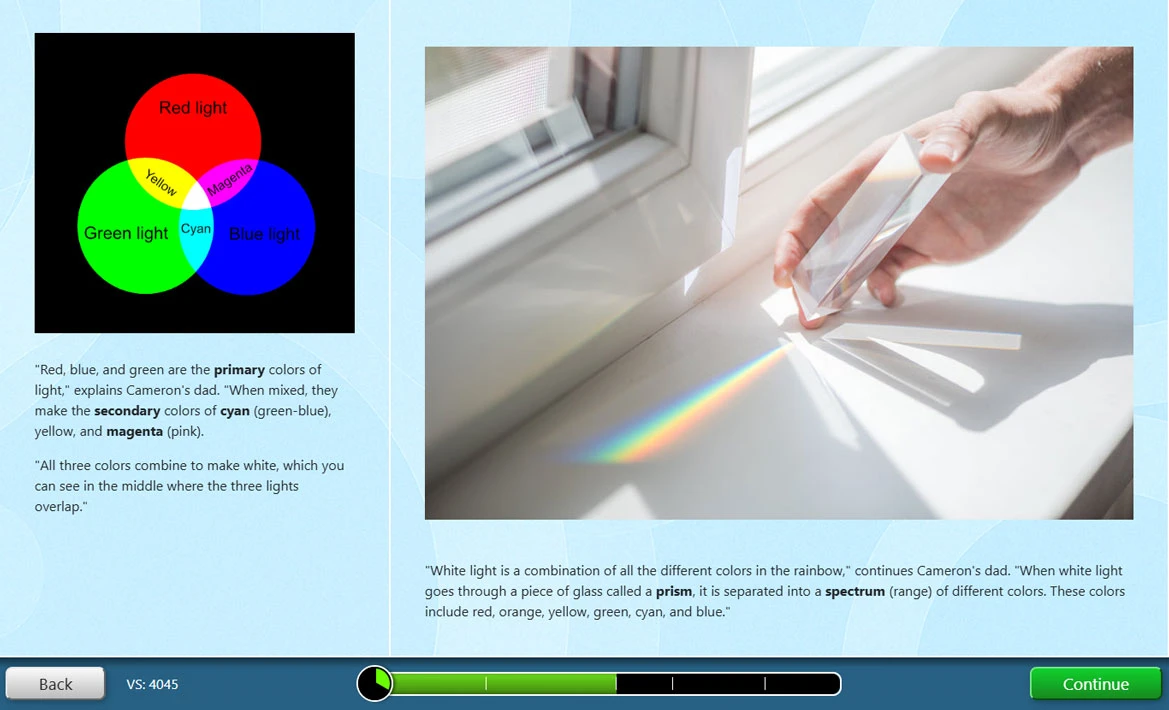

When you introduce light and color, help students see that the “white” light around them isn’t just one color but a blend of all the colors in the visible spectrum. A prism makes this idea concrete by spreading white light into red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet, giving students a visual anchor for how light is composed.

Students uncover white light in the Vision Investigation.

From there, you can trace the path of light through the eye. Light enters through the pupil, is focused by the lens, and lands on the retina, where specialized cells convert light into nerve signals. Rod cells support vision in low light but don’t detect color, while cone cells detect red, green, and blue. How do rod and cone cells work together? When stimulated by light, these cells transmit a nerve impulse that travels through the optic nerve to the visual cortex in the brain, where the image we perceive is created.

Different cone cells respond to different wavelengths, which is why we can distinguish colors—and why color vision varies across species. Most mammals only have two types of cone cells, while humans and other primates have three. This explains why tigers can remain hidden from their main prey.

Teach vision effectively with Gizmos Investigations

Gizmos Investigations are designed specifically for grades 6–8 to help students build critical thinking skills and master sensemaking practices through scaffolded, discovery-based lessons. The latest Vision Investigation guides learners through complex concepts such as the structure and function of the eye through interactive, real-world learning experiences.

Explore real-world phenomena through interactive models

Gizmos Investigations support inquiry-based learning and scientific sensemaking by anchoring abstract ideas in real-world questions and observable events. These scaffolded High-Quality Instructional Materials (HQIM) include built-in student questioning and just-in-time feedback to engage students in sensemaking practices at their individual levels of understanding as they work to solve real-life problems.

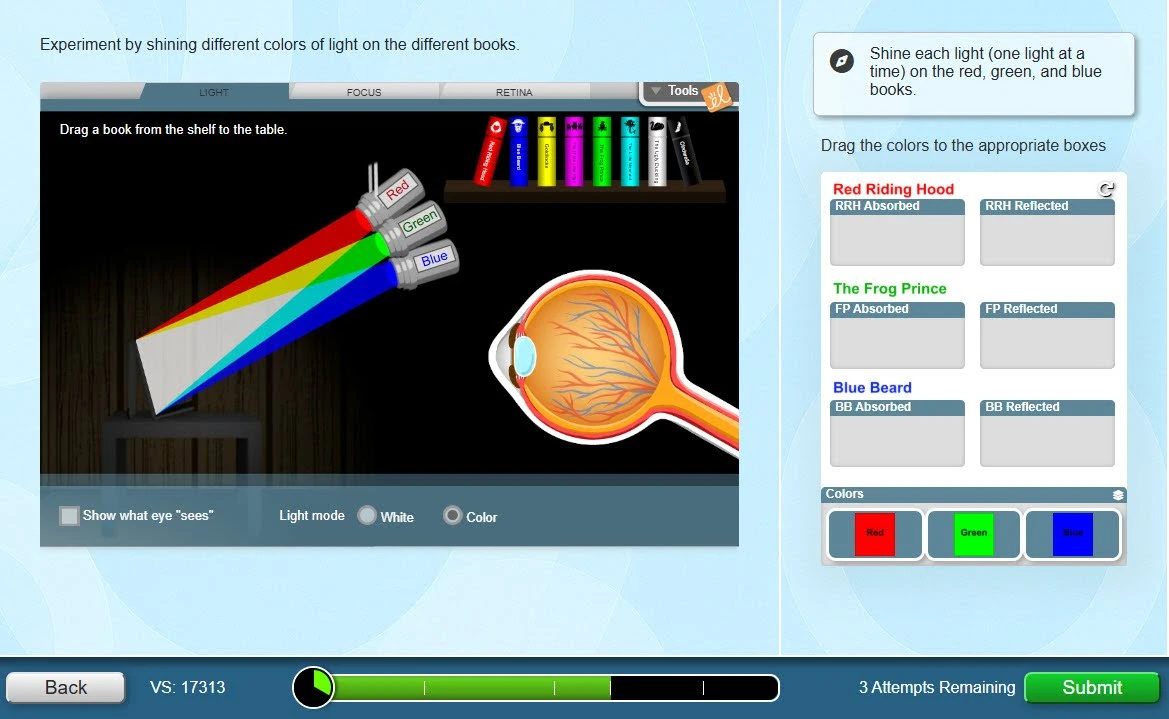

Gizmos Investigations make the invisible visible, while dramatically reducing prep time and increasing students’ conceptual understanding of vision. Instead of trying to grasp invisible processes, students manipulate variables directly as they adjust light levels, explore changes in cone and rod activity, and compare animal vision models.

Each Investigation wraps fully guided lessons around existing Gizmo simulations that teachers know and love, scaffolding sensemaking practices while guiding and assessing students as they solve problems. The Vision Investigation embeds existing Eyes and Vision simulations from the Gizmos library.

Supports middle school life & physical science standards

How does a bright orange tiger stay hidden from its prey while hunting? To answer this question, students learn how light is reflected from objects, how the human eye perceives color, and how human trichromatic vision differs from that of other mammals, including tigers and their prey.

The Vision Investigation aligns with middle school life and physical science standards and fits smoothly into units on vision, structure and function, and light waves. The investigation also connects naturally to broader life science collections, helping you build coherence across the year.

The multi-day Series Investigation is designed around multiple science practices found in NGSS and other state standards, including planning and carrying out investigations, analyzing and interpreting data, developing and using models, and constructing explanations.

By the end of the series, students will be able to:

- Create a model that shows how different colors of light are absorbed and reflected by different objects, and explain that the reflected light determines the color we see.

- Identify the parts of an eye and describe their functions.

- Observe how rod and cone cells in the retina respond to colors of light.

- Determine which cone cells are missing for tigers and their prey.

- Gather evidence to construct an explanation of why tigers see better than humans at night.

Two shorter, standalone lessons in the Vision Investigation provide real-world explorations that students can complete in one class period.

- Owl Eyesight: Students compare owl eyes to human eyes to determine how owls can see up to 100 times better than humans do at night.

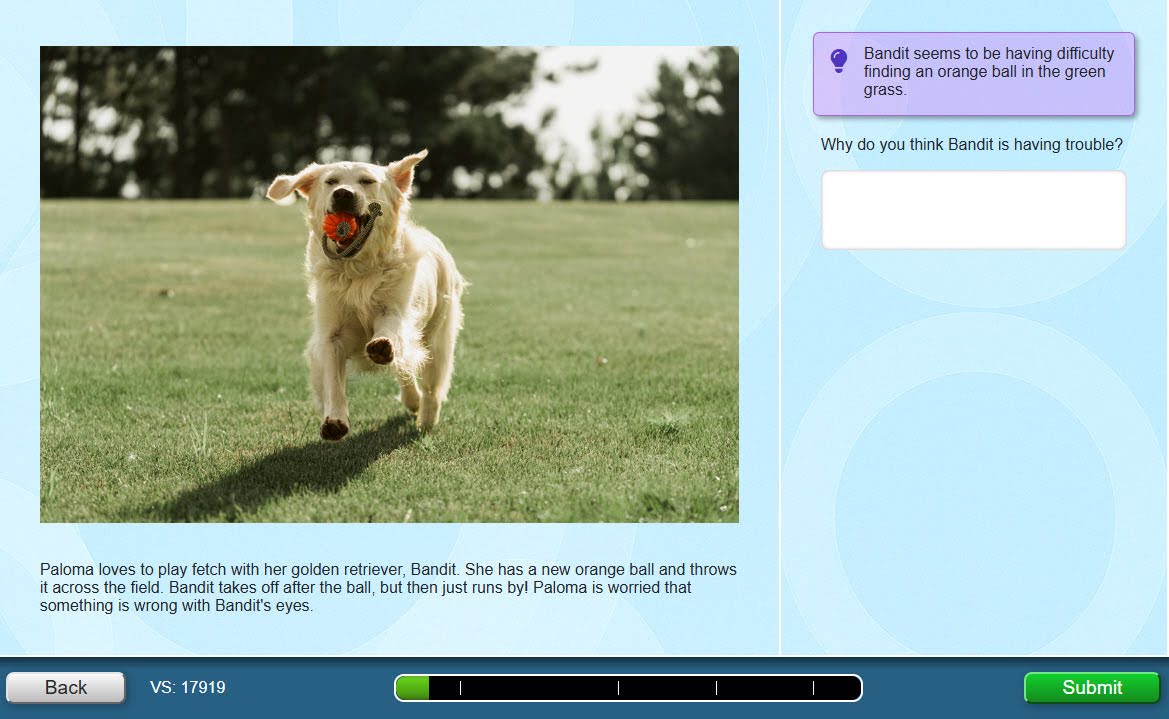

- Go Fetch: Students learn about how humans and animals see color using the cone cells in their eyes to find out why a dog can better fetch certain colored tennis balls.

Using CER to build strong scientific explanations

Interactive investigations are a natural fit for the Claim Evidence Reasoning (CER) framework because students can observe patterns, analyze results, and support their thinking with evidence, rather than just recalling facts. These supports give you built-in opportunities to move students from “what happened” to “why it happened.”

Guiding students from observation to explanation

The CER structure gives your students a consistent way to turn observations into scientific explanations. In investigation-based lessons like Gizmos Investigations, students can test ideas, gather data, and use their results as evidence to support a claim.

As students work, Gizmos Investigations scaffold their thinking with guided CER frameworks, prompts, and real-time feedback, helping them learn to connect their evidence to the underlying science concepts. For example, when thinking about vision, students might notice that tigers appear camouflaged to their prey (Claim). They then gather data from vision models to show that prey detect fewer colors (Evidence). At the end of an investigation, students conclude that prey see a limited color range, allowing the tiger’s stripes to blend into the environment rather than stand out (Reasoning).

Building in structured CER explanations into your lessons strengthens scientific reasoning and helps students practice arguing from evidence across your broader science units.

Try Gizmos Investigations to make teaching vision easy and engaging

Teaching vision doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. With Gizmos Investigations, you can turn complex ideas like colorblindness, light, eye structure, and animal adaptations into interactive experiences, helping your students test ideas, see patterns, and build understanding that sticks.

If you’re looking for an easy way to bring clarity and curiosity into your vision unit, explore the Vision Investigation today with a free Gizmos trial and unlock the entire Gizmos library for your students.