Tackle Thawing Permafrost in Alaska with Our New STEM Case

The latest ExploreLearning Gizmos STEM Case is about heat transfer and permafrost. It’s a critical STEM topic because thawing permafrost threatens the stability of crucial infrastructure in Arctic communities. In this interactive case study, Protecting Permafrost: Heat Transfer Highway, students assume the role of civil engineers to design and test solutions.

What is permafrost?

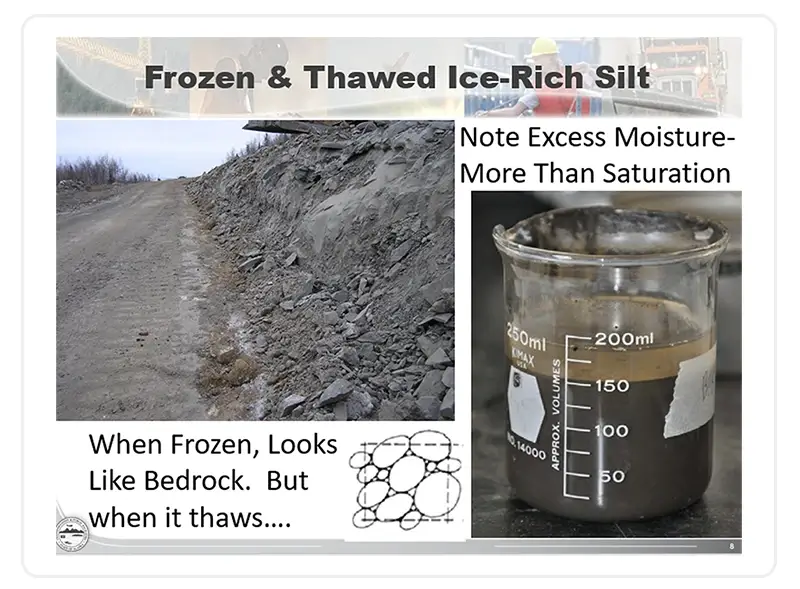

It’s easy to guess that permafrost in Arctic regions involves something cold, but what does it really mean? Permafrost definition is a layer of ground that remains frozen year-round for two or more years. Ground that stays colder than 32° F for at least two years is considered "perma"nently frozen. Get it? The layer, made up of permafrost soil, gravel, and sand, is typically bound together by ice and stays at or below 0° (32ºF). Above the permafrost is the active layer, which is ground that freezes and thaws seasonally with changes in air temperature.

Why is thawing permafrost important to know about?

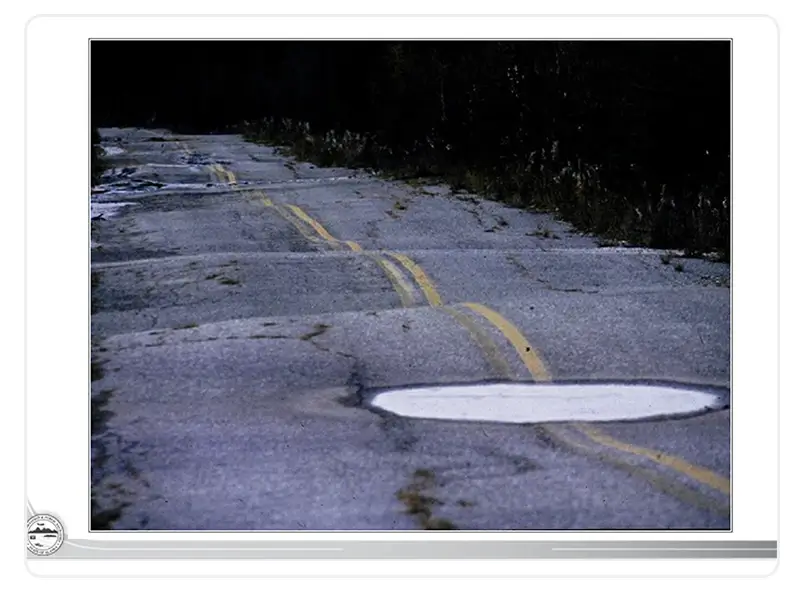

Permafrost is different from ice. Think of it this way. Ice melts like ice cubes turning into water. Permafrost thaws, similar to how a cook in the kitchen thaws frozen steaks. Permafrost is thawing as global warming causes the ground temperature of the Earth to warm. Thawing permafrost becomes a mixture of water and soil from the warmer ground temperatures, which can drastically impact the planet. The mushy soil leftover from freezing and thawing permafrost can’t support the weight of buildings, pipes, roads, or vegetation. As a result of freezes and thaws, infrastructure can be damaged because of unstable permafrost soil.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Currey

Permafrost in Alaska: Digging into this issue with Jeff Currey

Bringing in subject matter experts for the STEM Case development is critical to make the learning authentic. For this science simulation, ExploreLearning Learning Designer Carrie Adler enlisted the help of Jeff Currey, Northern Region Materials Engineer for the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Currey grew up in Southern California and went to the University of Alaska in Fairbanks to study mechanical engineering. Following college, he got into the mining industry and earned a second degree in mining engineering. His early work involved the mines of the Brooks Range in Alaska’s Arctic Region, and he got to see how permafrost behaves in an underground mining setting. “Now, as a materials engineer for the Department of Transportation (DOT), I supervise our hydraulic engineers, the engineering geologists, and the geotechnical engineers for the northern region and the entire state’s drilling program. We do geotechnical investigations for road, highway, and airport projects,” said Currey.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Currey

How did he learn about this STEM Case? “Carrie saw the Discover Alaska presentation that I did. She reached out to me and asked me if I would help as a subject matter expert, and I agreed to it,” said Currey. “After she got the draft of the case study, she basically gave me a presentation of that draft and asked me to review it. I caught a couple of things that could be improved. Overall, I was just super impressed. It’s artistic and contextually, it’s spot-on. There are people who get PhDs in permafrost at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and to capture so much of the concept and the treatment and the options in a two-hour program, I was pretty impressed.”

What was his favorite part of helping to develop the STEM Case? Currey said, “Seeing the animation for the time-lapse projections was pretty cool. To see the interactive animations as the viewer, you can manipulate the input and then watch it. It’s not pre-recorded. You have the ability to try different scenarios and manipulate the input. That was pretty cool.” Students can experience the work of STEM Case Digital Designers Zachary Davis, Renee Stander, Jenny Brewer, Jef Freydl, and Joel Rosenburg in those animations along with developer Christine de Carteret.

How students tackle permafrost thawing in Alaska with the latest STEM Case

In this STEM Case, aligned with Next Generation Science Standards for middle school grades, students act as civil engineers to design a solution to keep permafrost in Alaska cold and protect the stability of critical infrastructure. Set in the fictional town of Frostville, Alaska, a local climate monitor named “Aurora Borealis” serves as the guide.

Students are tasked with tackling how to protect permafrost in a warming climate. Working as civil engineers, students design a solution that mitigates heat transfer into fragile permafrost beneath an Alaskan town’s roads. The student identifies road sections at the most significant risk and implements multiple solutions to keep heat out of the permafrost, just as a STEM professional like Currey would do in the real world.

“When you build on permafrost, inevitably, there’s maintenance involved,” said Currey. “The frequency and extent of it has been increasing. As far as infrastructure is concerned, we do have techniques, as the STEM Case points out, that we can use to keep permafrost frozen or slow down its thawing to minimize maintenance. Most of those techniques rely on a long enough duration of cold in the wintertime to offset the summer thawing. As summers become longer and winters become shorter and not as cold, the net freezing effect is going to become less and less. And, for some of these techniques that we’re using, the effectiveness is going to deteriorate over time. So, what works well today may not work in fifty years.”

Key science concepts of heat transfer (conduction, convection, radiation), temperature, thermal energy, particle motion, and density are explored. By the end of the case, students will be able to explain how each of the three types of solutions applies heat transfer science concepts to protect permafrost below roads. Along the way, students test and compare materials for insulation and embankments, and they implement their solutions to see whether roads show damage.

Solutions in the STEM Case include:

- Insulation below roads (XPS and EPS, which are types of polystyrene boards)

- Air convection embankments (coarse gravel piles for road shoulders that allow heat to escape the ground through air currents between the rocks)

- Thermosiphons (giant pipes that extend into and above the ground, filled with compressed gases that remove heat from the permafrost)

Currey understands the importance of STEM education. “It would have been interesting to be introduced to more subjects. As a teenager, I didn’t know anything about permafrost. I learned that after moving to Alaska. The ability to dabble in different subjects and a wide range of subjects through these STEM Cases is pretty valuable.”

About Jeff Currey

Jeff Currey, P.E., has B.S. degrees in Mechanical Engineering and Mining Engineering, both from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He has been the Northern Region Materials Engineer for the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities since 2011, supervising the region’s drilling, engineering geology, geotechnical, and hydraulic engineering programs. He was a Northern Region Geotechnical Engineer for six years prior to that and started at DOT&PF in 2000 as a Highway Designer. Jeff worked in the mining and mineral exploration industry in Interior Alaska throughout the 1990s, including managing an underground placer mine and engineering several open-cut placer mines in ice-rich permafrost. He has lived in and around Fairbanks since 1986. A former dog musher, Jeff earned the Red Lantern (last finisher) award in the 1993 1,000-mile Yukon Quest sled dog race.