A Scientist’s Views on Thawing Permafrost and Its Impact

Permafrost isn’t just a research topic for Dr. Vladimir Romanovsky, Professor Emeritus of Geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. While most people live outside permafrost regions, he also lives where the impacts of thawing permafrost are practically and immediately important. “Be aware that it’s happening,” he said. “If climate changes, permafrost conditions will change as well.”

Meet the scientist: Dr. Vladimir Romanovsky

Dr. Romanovsky was always interested in science and mathematics, specifically in physics. “That’s why I got my Master’s degree in Geophysics from Moscow State University in Russia. By training, I’m a marine geophysicist. It just happened that permafrost study was very rapidly developing at that time, around 1975, when I got my first master's degree,” said Dr. Romanovsky. The department of permafrost proposed that he study permafrost as a geophysicist. “By that time, I had already found out that I was pretty seasick, and I really don't like the open water around you, so this proposition was interesting. I took the textbook about permafrost and read it.” That was a big turn in his career.

Photo credit: Dr. Vladimir Romanovsky

He earned another Master’s degree in Mathematics, and he didn’t stop there! “I got my PhD in Geology and became an Associate Professor at Moscow State. Another big turn was when I came here after being an Associate Professor at Moscow State University for seven years. I came here in 1992 as a graduate student and got my second PhD in Geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.”

As Professor Emeritus of Geophysics University of Alaska Fairbanks, he is now somewhat retired but still working. “I’m not doing teaching and administrative work, but fieldwork, writing, and reading are still the same,” said Dr. Romanovsky. He thinks the best parts of his duties are fieldwork, collecting data, and then trying to make sense of the collected data.

Why do scientists care about permafrost?

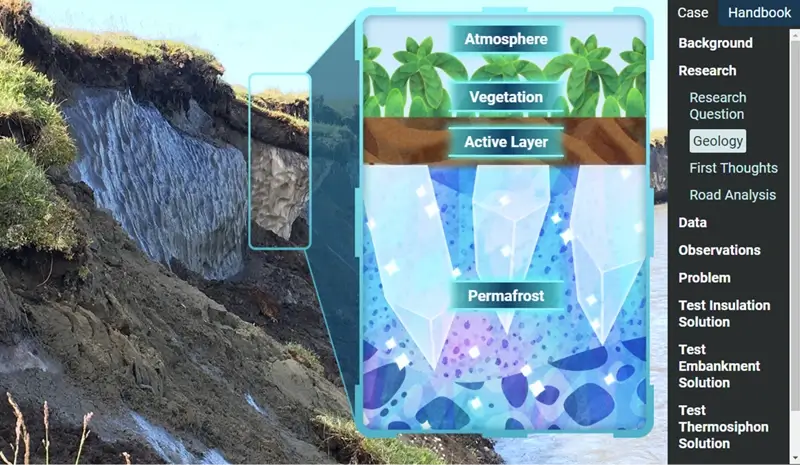

What’s permafrost? “The simplest and most logical definition of permafrost is any earth material, like soil or rocks or anything below the ground’s surface, that is frozen for two or more consecutive years. If you can prove that material is still frozen, you can call it permafrost,” said Dr. Romanovsky. The big question revolves around the concept of frozen, which brings some specific aspects to consider. “If the material continually has ice in it for two or more consecutive years, then you can call it permafrost. Or any earth material at or below 0 degrees Celsius for two or more consecutive years.” It’s important to note that this is not just frozen dirt. “You measure temperature in the ground, but it is complicated,” said Dr. Romanovsky.

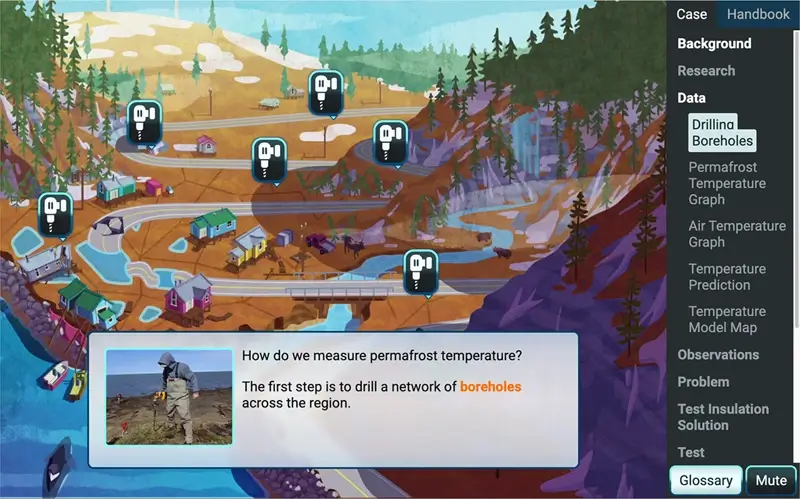

What tools are used to detect and measure permafrost? Sensors, such as temperature, soil, and moisture sensors, help scientists tell whether an area is frozen or not frozen. “The main tool is temperature sensors. We drill holes in the ground at different depths and put sensors in those holes to measure temperature– sometimes continuously, sometimes at different times throughout the year,” said Dr. Romanovsky. “Almost everywhere, there is an upper layer above the permafrost that is thawing in the summer and refreezing completely in winter. Some holes we’ve had since the late 1970s, so we have already almost 50 years at the same location to see how permafrost changes.”

What else do scientists have to consider? “If the hole has a small diameter, it doesn’t impact the temperature in the ground. If it’s almost 0, it’s not permafrost. If it’s frozen during the winter but not frozen during the summer, it’s not permafrost.”

What are the impacts of thawing permafrost?

Permafrost is a product of cold climates. Dr. Romanovsky said, “You really need to have a cold enough climate, pretty much the air temperature. Permafrost can be found in high latitudes, Arctic, Subarctic, and Antarctic. It’s also found in places with high elevations, even in the lower latitudes. Kilimanjaro, for example, is almost on the equator but still has permafrost.”

While permafrost can be found in the high latitudes of both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres and the high elevations, it’s difficult to estimate the total area because of discontinuous permafrost, which are places that can have permafrost and non-permafrost in the same location. “The farther north you go, permafrost will be everywhere,” said Dr. Romanovsky. “On the North Slope in Alaska or in high elevations of Antarctica, you know you will pretty much find permafrost everywhere. Going south, permafrost is less and less in continuous distribution. In the Anchorage area, there’s practically no permafrost, but you can find some in specific locations with specific surface conditions.”

Climate changes cause changes in permafrost conditions as well. “As the climate gets warmer and warmer, or not cold enough to support stable permafrost, it will start to thaw, mostly from the top down,” said Dr. Romanovsky. “The layer that thaws will get thicker and thicker. It could thaw at a rate of 5-15 cm per year.”

That means anything sensitive to changes from ice to water can be affected by the thawing of permafrost. Dr. Romanovsky said, “The water will drain out, causing changes in the surface, which will affect anything sitting on the surface– roads, buildings, airstrips. This is a major problem for infrastructure because it is rigid.”

“There are other things that we cannot see, such as microorganisms, that will be affected,” said Dr. Romanovsky. When frozen, they cannot move or mobilize. As permafrost thaws, those microorganisms could penetrate other living things. “For example, the consumption of the organic material, which is now frozen, would be available for animal digestion. A product of that would be greenhouse gasses, which will accelerate warming and thawing,” he said.

Ways to help stop the thawing of permafrost

Preserving permafrost depends on future climate change. If air temperature increases by 7-8 degrees Celsius (44.6- 46.4 degrees Fahrenheit), permafrost is expected to start to thaw. “Most of the effects will be negative effects on human activities,” said Dr. Romanovsky. “Even now, there are villages considering a move to other locations because of changes happening.”

Is there any safe place from permafrost melting to build infrastructure and set up buildings? “In Greenland, it won’t be as big a problem because they build their houses on bedrock,” said Dr. Romanovsky. “In northern Alaska, it will be a big, big problem because there are very few locations to find hard material, bedrock, near the surface. It will be changing under the infrastructure, under the roads, and in airports; everything will be impacted in a negative way. There will be centuries of mess before it will be more stable again.”

“Because thawing permafrost is so widespread, there’s pretty much no way to stop this on a landscape scale. The only thing to help is to stop climate change. Then, you’ll preserve permafrost. Locally, there are some engineering solutions to help. It’s very difficult on a landscape scale, almost impossible,” said Dr. Romanovsky. Developing mitigation strategies to lessen the effects is critical.

Permafrost melting: Explore permafrost and more in this STEM Case

Dr. Romanovsky hopes students will find materials to satisfy their interest in science and become critical thinkers. “Dig deeper, find an explanation why these things are happening, and then dig even deeper,” he said.” Find out about the chemical, physical, and biological processes behind these processes– that’s what scientists do.”

Protecting Permafrost: Heat Transfer Highway STEM Case

Using Gizmos STEM Cases, students can dig deeper and act as real scientists, like Dr. Romanovsky. In the Protecting Permafrost: Heat Transfer Highway STEM Case, students investigate realistic solutions to tackle the problems caused by thawing permafrost while exploring data and variables for designing solutions and monitoring their effectiveness. Dr. Romanovsky’s expertise and knowledge provided valuable insights into the creation of this STEM Case.

Protecting Permafrost: Heat Transfer Highway STEM Case

Are your students ready to explore solutions to protect permafrost?

Looking for more opportunities for your students to act as scientists? Take a Gizmos trial.

Start My Trial